Heatwaves: Lessons from India on dealing with this growing hazard

Europe is in the midst of a powerful heatwave that has already broken records. The “unusually early and exceptionally intense heatwave,” according to the World Meteorological Organization, has caused France to record its highest all-time temperature of 45.9° C. A number of countries in Europe experienced their hottest June on record, bringing memories of the August 2003 heatwave that caused the death of an estimated 70,000 people across Europe.

Globally, hot days are getting hotter and more frequent. Since 1880, five of the warmest years on record occurred from 2014 to 2018, with 2019 so far on course to be among the world’s years ever. This warming trend is expected to continue since human activity is adding more greenhouse gas emissions that are trapping heat in the atmosphere. As a result, global warming has led to a worldwide increase in the frequency, intensity and duration of extreme heat events or heatwaves.

Heatwaves are a significant but under-estimated emerging hazard. While heatwaves and hot weather do not cause significant damage to the landscape similar to cyclones and earthquakes, the impacts of heatwaves on health, economic productivity, and the environment can nonetheless be serious and costly.

Cities are more vulnerable to heatwaves than rural areas because of what is known as the “urban heat island” effect, which can cause temperatures to be 1 to 3°C hotter than in surrounding areas. This phenomenon occurs because of a decreased amount of vegetation and increased areas of dark surfaces in urban environments, in addition to the heat produced from vehicles, generators, and ironically, the waste heat from the air conditioners.

While the criteria for declaring a heatwave varies by country and region, the impact of excess heat on the human body is universal. Our bodies operate at a core temperature of 37°C. If body temperature rises to 38°C for several hours, heat exhaustion occurs, and mental and physical capacity becomes impaired. If the core temperature goes above 42°C, even for just a few hours, heat stroke and death can result, especially among vulnerable groups such as the elderly, young children, those working outdoors, and patients with chronic diseases.

One country that has traditionally experienced high mortality from heatwaves is India. From 1992 to 2016, heatwaves caused 25,716 deaths across India. In 2015, the number of people seeking medical help for heat-related ailments was so high that authorities in one state reportedly cancelled doctors’ leave. By the end of the summer of 2015, 2,040 people had died because of heat. Last year, India again experienced intense heat, with reports of temperatures in some areas exceeding 50°C. However, the final death toll for 2018 was 25 deaths. That is a decline of more than 98 percent in three years.

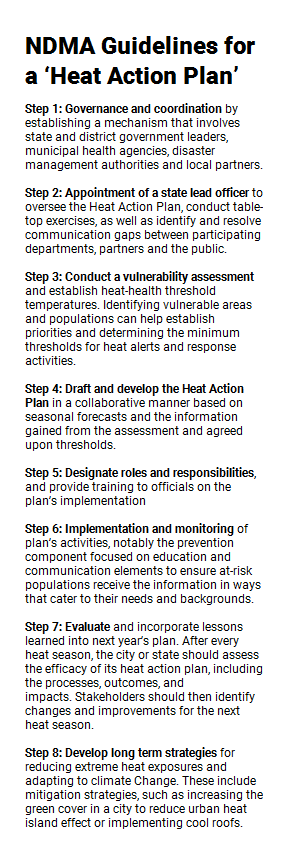

This significant decrease is credited to actions taken by state authorities and India’s National Disaster Management Agency (NDMA). In 2012, the city of Ahmadabad in the state of Gujarat became the first Indian city to start developing a heatwave action plan. In 2016, building on state-level experiences and a body of research conducted in India and abroad, the NDMA circulated to state disaster management agencies its ‘Guidelines for Preparation of Action Plan - Prevention and  Management of Heat-Wave,’ which included a framework for planning, implementing and evaluating activities to reduce the adverse effects of extreme heat.

Management of Heat-Wave,’ which included a framework for planning, implementing and evaluating activities to reduce the adverse effects of extreme heat.

State authorities subsequently used these guidelines to develop their own annual ‘Heat Action Plans’. These plans adopt a whole-of-society approach and seek partnerships with various local agencies and organizations, including hospitals, schools and the media.

Since 2015, UNDP India has been providing support to states and districts to help them develop and implement their plans. Mr. Sattar Abdul, a Disaster Risk Reduction Specialist with UNDP, said: “one of the key factors for the success of India’s local Heat Action Plans is that states take a systematic approach and activities are broken into three stages, before, during and after the heatwave. Moreover, they engage a wide segment of society and various line ministries.”

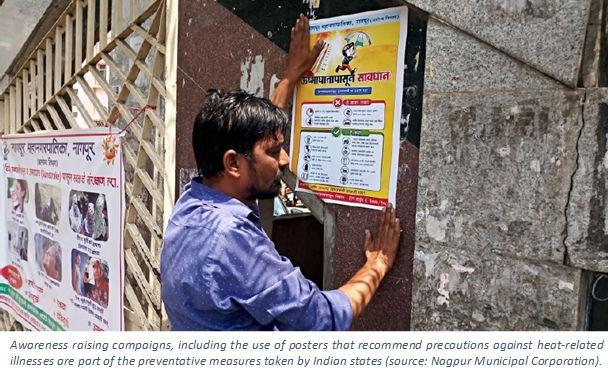

While plans differ in some details based on local circumstances, they all emphasize prevention and bolstering local capacity to intervene when needed. Specifically, the plans call for the development of a heat early warning system. Once a threshold is reached, the system would alert city and state authorities to activate mitigation measures. Alerts would also be broadcast to the public and would be coupled with a communication campaign aimed at at-risk populations. The dissemination of alerts occurs through mobile text messages, posters, electronic billboards, and the use of local media. In 2018, the NDMA launched a national television and social media campaign, Beat the Heat India, which helped raise community awareness on extreme heat to protect individuals, families, and vulnerable groups.

Indian states also developed mitigation measures to help those inflicted or at-risk, such as:

- Establishing drinking water kiosks at high-risk areas such as open markets, construction sites and bus stations.

- Expanding access to shaded areas and shelters for outdoor workers, slum communities, and other vulnerable people.

- Setting up medical camps and stocking oral rehydration salts (ORS) packets.

- Training medical staff and employers to recognize the signs and danger of heat strokes.

In 2018, states and cities adopted these measures to achieve their target of reducing the impact of heatwaves on people and reduce the number of deaths. Examples include:

-

State of Andhra Pradesh

The state released a ‘Heat Wave Atlas’ that identified local heatwave hot spots and set up 1,168 automatic weather stations (AWS) – approximately one for every hundred square kilometres, which provided daily heat forecasts for all administrative zones within districts. Through a bilingual (Telegu and English) mobile app, these forecasts have reportedly reached thousands of people.

The state also worked with non-governmental organizations to set up over 60,000 drinking water kiosks, organized 70,000 shelters and distributed 1.24 million packets of ORS and over 220,000 heat awareness pamphlets.

-

State of Maharashtra

The state health department issued a list of ‘Do’s and Don’ts’ to all hospitals and primary health centres across the state to raise the awareness of medical staff. The state changed school times, established drinking water spots, provided shelter for traffic police, altered duty hours of state personnel above the age of 45, and prepared ‘cold wards’ at hospitals.

One NDMA recommendation that is now gaining traction among local and state officials is on the need to adopt long-term risk reduction measures. Speaking at a national workshop on heatwaves in February 2019, NDMA Joint Secretary, Dr. V. Thiruppugazh said: “We must not only aim towards zero heat mortality and reduced illnesses, but also heatwave risk reduction.”

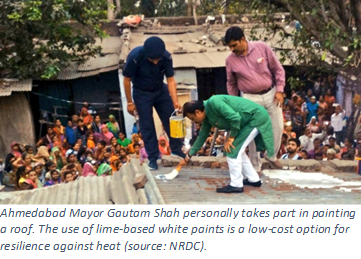

These risk reduction measures often call for changes to the structural and urban environment to reduce the urban heat island effect and the impact of heatwaves on vulnerable groups. Examples of such measures include the use of cool roofs, cool pavements, vegetation and trees, and traffic reduction strategies. Cool roofs use reflective paint, tiles or vegetation to minimize the amount of absorbed heat. Dark asphalt reflects only 4 percent of sunlight compared to as much as 25 percent for natural grass and up to 90 per cent for a white surface. Cool roofs and pavements also reduce electricity demand, resulting in cost savings and lessening of the load on the electric grid during a heatwave.

One city that has been pioneering the use of such measures is the city of Ahmedabad in Gujarat. Last year the city expanded the use of cool roofs by applying reflective paint on buildings citywide. Working with the Gujarat Institute of Disaster Management (GIDM), the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation introduced a cool roof initiative to provide affordable cooling for those who are most vulnerable to the health effects of extreme heat. This included the use of wet gunny sacks on the roofs of slums for evaporative cooling, which was an effort promoted by the Mayor of Ahmedabad in a city-wide public awareness campaign.

One city that has been pioneering the use of such measures is the city of Ahmedabad in Gujarat. Last year the city expanded the use of cool roofs by applying reflective paint on buildings citywide. Working with the Gujarat Institute of Disaster Management (GIDM), the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation introduced a cool roof initiative to provide affordable cooling for those who are most vulnerable to the health effects of extreme heat. This included the use of wet gunny sacks on the roofs of slums for evaporative cooling, which was an effort promoted by the Mayor of Ahmedabad in a city-wide public awareness campaign.

Mr. P.K. Taneja, the Direct General of GIDM, said: “The increased frequency and intensity of heatwaves has posed the urgent need for mitigation measures in Gujarat. Given the impacts of heatwaves, it is crucial to understand the exposed population and accordingly build their capacities towards its physiological and psychological impacts. With the use of technology, masses can be sensitized, and major impacts can be mitigated.”

Beyond these adaptive measures, cities can also take advantage of their topography and building codes to reduce the risk of intense urban heat. The German city of Stuttgart, for example, has implemented targeted interventions such as a building ban in the hills around the city and the prevention of building projects that might obstruct the ventilation effect of evening cold-air flows. These interventions have resulted in the preservation and enhancement of air exchange and cool air flows in the city, which not only lessens the impact of heat but also reduces air pollution.

The 5th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change indicated that an increase in the frequency, length and intensity of heatwaves will be “very likely over most land areas” well into the future. Therefore, as global warming increases, it is important that cities consider how they will integrate disaster risk reduction measures against heatwaves into their long-term development plans.

Explore further

Also featured on

Is this page useful?

Yes No Report an issue on this pageThank you. If you have 2 minutes, we would benefit from additional feedback (link opens in a new window).